Paper review & code: Set Transformer

Set Transformer, ICML 2019

** Click here for the companion Python package on Github **

In a previous post I talked about functions preserving permutation invariance with respect to input data (i.e. sets of data points such as items in a shopping cart). If you are not familiar with this concept please review that post or refer to the original DeepSet paper.

In this post we will go through the details of a recent paper that leverages the idea of attention and the overall transformer architecture to attain input permutation invariance, and solves some of the shortcomings connected with the naive pooling operation we used in DeepSets. You can find the original publication by Lee et al. here: Set Transformer: A Framework for Attention-based Permutation-Invariant Neural Networks.

In the DeepSet publication the authors suggest to use a simple pooling function (sum or mean) to combine together different branches of a neural network (each one processing one data point independently but with shared weights). Although this simple solution effectively works as intended, by pooling different vectors together we are ‘squashing’ the information contained in source data and losing information about higher-order interactions which may exist among members of the set. The Set Tranformer architecture suggested in the aforementioned publication tackles these shortcomings by providing a richer representation of input data that capture higher-order interactions and parametrizes the pooling operation so that no information is lost after combining data points.

Disclaimer: the code reported below is meant to be executed in the Docker container reported in the companion Python package on Github:

https://github.com/arrigonialberto86/set_transformer . See the docs on the repo on how to use docker-compose.yml to try this in a Jupyter Notebook.

Paper contributions

It has been observed before that the transformer architecture (here you can find a very nice ‘visual’ introduction to Transformer) without positional encoding does not retain information regarding the order by which the input words are being supplied. Thus, it makes sense to suppose that the attention mechanism (which constitutes the basis of the Transformer architecture) could be used to process sets of elements in the same way as we have seen for the DeepSet architecture. In Lemma 1 of the their paper, Lee et al. demonstrate that the mean operator (i.e. the pooling function we have used in the previous blog post) is a special case of dot-product attention with softmax (i.e. the self-attention mechanism). If this sounds strange to you (or, on the other hand, too simple to be true) I can provide an informal explanation of what self-attention is, and why it matters in so many different contexts.

Let us say we have a set of f-dimensional elements/vectors (in the classical NLP context these would be one-hot-encoded vectors to be subsequently

projected down to an embedding space, here just feature vectors). Since we are processing sets we do not care about the order,

just know that we have a n x f input matrix N. We project this matrix into 3 separate new matrices that are referred to as keys (K), queries (Q), and values (V).

The projection matrices will be learned during training just like any other parameters in the model. During training the projection matrices will learn how to produce queries,

keys and values that will lead to optimal attention weights.

Let us just take a pair of feature vectors to make this concrete (and hopefully clearer): vector a and b both defined in .

We now use the three projection matrices K, Q and V (which are all trainable as said before) to obtain three versions (possibly very different according to parametrization)

of the input vector

a, i.e. a_Q, a_K, a_V, whose dimensionality depends on K, Q, and V (their dimension is an hyperparameter that needs tuning).

We do the same thing for b to obtain b_Q, b_K, b_V (i.e. the two-vector set ({a, b}) has now been converted to two lists of vectors).

What we would like to understand with these operations (the whole attention mechanism) is how much a is related to itself and b, or put in other terms:

do I need b when predicting a target related to a or all the information I need is already present in a?

We can calculate how much a is related to itself by multiplying (via the inner product) its query (a_q) and key (a_k) together.

Remember, we compute all pairwise interactions between nodes including self-interactions and unsurprisingly objects are likely to be related to themselves,

but not necessarily since the corresponding queries and keys (after projection) may be different.

What we get by the queries (Q) and keys (K) product is a unnormalized attention weight matrix, which we later normalize by using a softmax function. Once we have the normalized attention weights, we then multiply these by the corresponding value matrix (V) to focus on only certain salient parts of the value (V) matrix, and this will give us a new and updated node matrix:

The QK^T matrix is a nxn matrix which encodes the pairwise relationships between the elements of the input set.

We then multiply this by the value (V) matrix, which will update each feature vector according to its interactions with other elements, such that the final result is an updated set matrix.

What is truly remarkable about this encoding process is that it is flexible enough to be useful in very different contexts: in NLP (where attention was conceived)

the weight matrix represents how much one word is relevant for the translation of another word, i.e. the contextual information, in graph neural network the QK^T matrix

becomes the weighted adjacency matrix of the graph (more on this here).

Let us put these words into code:

import tensorflow as tf

# https://www.tensorflow.org/tutorials/text/transformer, appears in "Attention is all you need" NIPS 2018 paper

def scaled_dot_product_attention(q, k, v, mask):

"""Calculate the attention weights.

q, k, v must have matching leading dimensions.

k, v must have matching penultimate dimension, i.e.: seq_len_k = seq_len_v.

The mask has different shapes depending on its type(padding or look ahead)

but it must be broadcastable for addition.

Args:

q: query shape == (..., seq_len_q, depth)

k: key shape == (..., seq_len_k, depth)

v: value shape == (..., seq_len_v, depth_v)

mask: Float tensor with shape broadcastable

to (..., seq_len_q, seq_len_k). Defaults to None.

Returns:

output, attention_weights

"""

matmul_qk = tf.matmul(q, k, transpose_b=True) # (..., seq_len_q, seq_len_k)

# scale matmul_qk

dk = tf.cast(tf.shape(k)[-1], tf.float32)

scaled_attention_logits = matmul_qk / tf.math.sqrt(dk)

# add the mask to the scaled tensor.

if mask is not None:

scaled_attention_logits += (mask * -1e9)

# softmax is normalized on the last axis (seq_len_k) so that the scores

# add up to 1.

attention_weights = tf.nn.softmax(scaled_attention_logits, axis=-1) # (..., seq_len_q, seq_len_k)

output = tf.matmul(attention_weights, v) # (..., seq_len_q, depth_v)

return output, attention_weights

From here it is easy (at least conceptually) to extend our framework to multi-head attention: instead of having a single attention function,

this method projects Q,K and V onto h different triplets of vectors.

An attention function is applied to each of these h projections and the output is a linear transformation of the concatenation of all attention outputs.

For an implementation of multihead attention see here.

For simplicity, we define the Multihead function, which receives Q, K, V, parameters w and returns the encoded vector (for a dimensionality

check on input/output vectors you may want to reference these unit tests I wrote

for the package).

The network structure

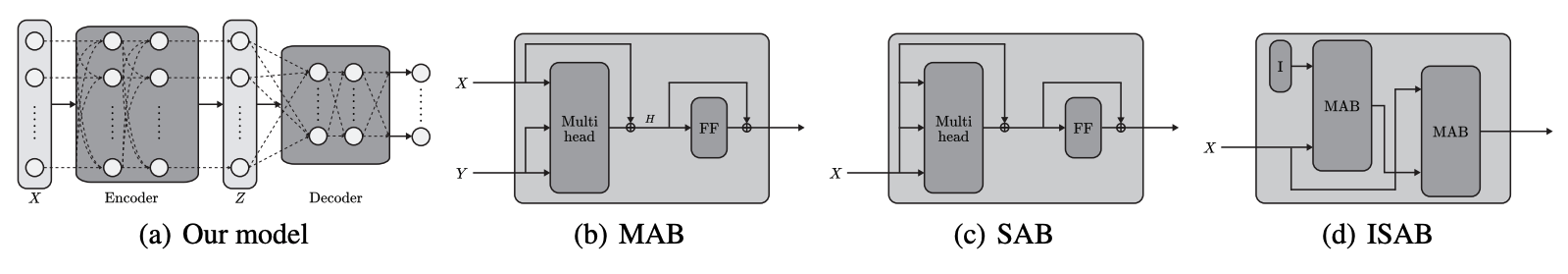

The network structure proposed by Lee et al. closely resembles a Transformer, complete with an encoder and a decoder network, but a distinguishing feature is that each layer in the encoder and decoder attends to their inputs to produce activations.

The encoder and the decoder are built by almost the same building blocks, the main difference is that in the decoder they introduce a block that performs pooling by using a parametric function (a neural network) (PMA), so that it can model more complex relationships than the mean operator used elsewhere. These are the building blocks of their model:

ENCODER = SAB(SAB(X)) with output Z, input of the decoder

DECODER = rFF(SAB(PMA(Z)))

In the following sections we go through the list of building blocks of the network and present an informal definition and implementation.

Permutation equivariant Set Attention Blocks (SAB)

Since we are using self-attention to concurrently encode the whole set of input data, we define a Multihead Attention Block (MAB) with parameters w (as in the publication).

Given input matrices X and Y (both of dimensionality n x d) we define a MAB as:

MAB(X, Y) = LayerNorm(H + RFF(H))

where H = LayerNorm(X + Multihead(X,Y,Y; w))

rFF is any row-wise feedforward layer and LayerNorm is (of course) layer normalization. An rFF can be implemented like this:

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Dense

class RFF(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

"""

Row-wise FeedForward layers.

"""

def __init__(self, d):

super(RFF, self).__init__()

self.linear_1 = Dense(d, activation='relu')

self.linear_2 = Dense(d, activation='relu')

self.linear_3 = Dense(d, activation='relu')

def call(self, x):

"""

Arguments:

x: a float tensor with shape [b, n, d].

Returns:

a float tensor with shape [b, n, d].

"""

return self.linear_3(self.linear_2(self.linear_1(x)))

With the MAB in place (which is just an adaptation of the encoder block of the Transformer but without positional encoding) we can now define the Set Attention Block (SAB):

SAB(X) := MAB(X, X)

And this is a SAB layer implementation:

class SetAttentionBlock(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, d: int, h: int, rff: RFF):

super(SetAttentionBlock, self).__init__()

self.mab = MultiHeadAttentionBlock(d, h, rff)

def call(self, x):

"""

Arguments:

x: a float tensor with shape [b, n, d].

Returns:

a float tensor with shape [b, n, d].

"""

return self.mab(x, x)

You may have noticed a scalability issue with this implementation: for set structured data we need to derive an all-vs-all matrix of weights which results

in an algorithm of complexity ().

The authors come up with a clever way to reduce this complexity to

,

where

m is the dimensionality of trainable ‘inducing points’. These ‘inducible’ vectors are in fact parameters that are learned during training

along with all the others. You may picture this operation as making a low-rank projection or using an under-complete autoencoder model.

Let us slightly modify our SAB implementation to obtain an ISAB:

class InducedSetAttentionBlock(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, d: int, m: int, h: int, rff1: RFF, rff2: RFF):

"""

Arguments:

d: an integer, input dimension.

m: an integer, number of inducing points.

h: an integer, number of heads.

rff1, rff2: modules, row-wise feedforward layers.

It takes a float tensor with shape [b, n, d] and

returns a float tensor with the same shape.

"""

super(InducedSetAttentionBlock, self).__init__()

self.mab1 = MultiHeadAttentionBlock(d, h, rff1)

self.mab2 = MultiHeadAttentionBlock(d, h, rff2)

self.inducing_points = tf.random.normal(shape=(1, m, d))

def call(self, x):

"""

Arguments:

x: a float tensor with shape [b, n, d].

Returns:

a float tensor with shape [b, n, d].

"""

b = tf.shape(x)[0]

p = self.inducing_points

p = repeat(p, (b), axis=0) # shape [b, m, d]

h = self.mab1(p, x) # shape [b, m, d]

return self.mab2(x, h)

We now have all the ingredients/blocks to write the encoder layer of our model:

class STEncoder(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, d=12, m=6, h=6):

super(STEncoder, self).__init__()

# Embedding part

self.linear_1 = Dense(d, activation='relu')

# Encoding part

self.isab_1 = InducedSetAttentionBlock(d, m, h, RFF(d), RFF(d))

self.isab_2 = InducedSetAttentionBlock(d, m, h, RFF(d), RFF(d))

def call(self, x):

return self.isab_2(self.isab_1(self.linear_1(x)))

Pooling by Multihead Attention (PMA block)

We said before that feature aggregation is commonly performed by dimension-wise averaging. The authors propose instead to apply multihead attention

on a learnable set of k seed vectors (S). The idea is not dissimilar to what we saw for ISAB and has the following structure (remember that Z is the encoder’s output):

PMA(Z) = MAB(S, rFF(Z))

To complete the decoder layer, we apply a SAB on the output of PMA:

H = SAB(PMA(Z))

The implementation of the Multihead Attention Block (MAB) looks like this:

class PoolingMultiHeadAttention(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, d: int, k: int, h: int, rff: RFF, rff_s: RFF):

"""

Arguments:

d: an integer, input dimension.

k: an integer, number of seed vectors.

h: an integer, number of heads.

rff: a module, row-wise feedforward layers.

It takes a float tensor with shape [b, n, d] and

returns a float tensor with the same shape.

"""

super(PoolingMultiHeadAttention, self).__init__()

self.mab = MultiHeadAttentionBlock(d, h, rff)

self.seed_vectors = tf.random.normal(shape=(1, k, d))

self.rff_s = rff_s

@tf.function

def call(self, z):

"""

Arguments:

z: a float tensor with shape [b, n, d].

Returns:

a float tensor with shape [b, k, d]

"""

b = tf.shape(z)[0]

s = self.seed_vectors

s = repeat(s, (b), axis=0) # shape [b, k, d]

return self.mab(s, self.rff_s(z))

The resulting decoder looks like this:

class STDecoder(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, out_dim, d=12, h=2, k=8):

super(STDecoder, self).__init__()

self.PMA = PoolingMultiHeadAttention(d, k, h, RFF(d), RFF(d))

self.SAB = SetAttentionBlock(d, h, RFF(d))

self.output_mapper = Dense(out_dim)

self.k, self.d = k, d

def call(self, x):

decoded_vec = self.SAB(self.PMA(x))

decoded_vec = tf.reshape(decoded_vec, [-1, self.k * self.d])

return tf.reshape(self.output_mapper(decoded_vec), (tf.shape(decoded_vec)[0],))

A toy problem: maximum value regression

To show the advantage of attention-based set aggregation over simple pooling operations, the authors consider regression to the maximum value of a given set. Let us generate a random dataset to be used for learning:

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

def gen_max_dataset(dataset_size=100000, set_size=9, seed=0):

"""

The number of objects per set is constant in this toy example

"""

np.random.seed(seed)

x = np.random.uniform(1, 100, (dataset_size, set_size))

y = np.max(x, axis=1)

x, y = np.expand_dims(x, axis=2), np.expand_dims(y, axis=1)

return tf.cast(x, 'float32'), tf.cast(y, 'float32')

And then using the APIs from the set_transformer package we can write:

from set_transformer.data.simulation import gen_max_dataset

from set_transformer.model import BasicSetTransformer

import numpy as np

train_X, train_y = gen_max_dataset(dataset_size=100000, set_size=9, seed=1)

test_X, test_y = gen_max_dataset(dataset_size=15000, set_size=9, seed=3)

set_transformer = BasicSetTransformer()

set_transformer.compile(loss='mae', optimizer='adam')

set_transformer.fit(train_X, train_y, epochs=3)

predictions = set_transformer.predict(test_X)

print("MAE on test set is: ", np.abs(test_y - predictions).mean())

which quickly results in :

Train on 100000 samples

Epoch 1/3

100000/100000 [==============================] - 27s 270us/sample - loss: 32.8959

Epoch 2/3

100000/100000 [==============================] - 20s 197us/sample - loss: 6.6131

Epoch 3/3

100000/100000 [==============================] - 22s 216us/sample - loss: 6.4121

MAE on test set is: 6.558687

You can go ahead and compare the results obtained with this approach with the other architectures employing mean and max pooling operations.

Notably, the authors report that the Set Transformer achieves performance comparable to the max-pooling model

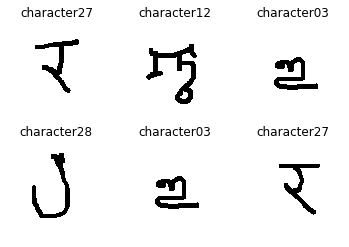

Counting unique characters

In this example I will just set the stage for a run using the set_transformer APIs. The reference dataset is called ‘Omniglot’,

which consists of 1,623 different handwritten characters from various alphabets, where each character is represented by 20 different images.

Characters are sampled at random from this dataset and the task at hand is to predict the number of unique characters present in the input set.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from tqdm.notebook import tqdm

from typing import List

# Get list of different character paths

img_dir = './images_background'

alphabet_names = [a for a in os.listdir(img_dir) if a[0] != '.'] # get folder names

char_paths = []

for lang in alphabet_names:

for char in [a for a in os.listdir(img_dir+'/'+lang) if a[0] != '.']:

char_paths.append(img_dir+'/'+lang+'/'+char)

char_to_png = {char_path: os.listdir(char_path) for char_path in tqdm(char_paths)}

def draw_one_sample(char_paths: List, sample_size=6):

n_chars = np.random.randint(low=1, high=sample_size, size=1)

selected_chars = np.random.choice(char_paths, size=n_chars, replace=False)

rep_char_list = selected_chars.tolist() + \

np.random.choice(selected_chars, size=sample_size-len(selected_chars), replace=True).tolist()

sampled_paths = [char_path+'/'+np.random.choice(char_to_png[char_path]) for char_path in rep_char_list]

return sampled_paths, n_chars[0]

sampled_paths, n_chars = draw_one_sample(char_paths, sample_size=6)

And that is what a random sample looks like:

from matplotlib.figure import Figure

from numpy import ndarray

from typing import List

import matplotlib.image as mpimg

def render_chart(fig: Figure, axis: ndarray, image_id: int, data_list: List):

image = mpimg.imread(data_list[image_id])

axis.title.set_text(data_list[image_id].split('/')[-2])

axis.axis('off')

axis.imshow(image, cmap='gray')

print('Number of selected characters is {}'.format(n_chars))

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 3)

render_chart(fig=fig, axis=axs[0, 0], image_id=0, data_list=sampled_paths)

render_chart(fig=fig, axis=axs[0, 1], image_id=1, data_list=sampled_paths)

render_chart(fig=fig, axis=axs[0, 2], image_id=2, data_list=sampled_paths)

render_chart(fig=fig, axis=axs[1, 0], image_id=3, data_list=sampled_paths)

render_chart(fig=fig, axis=axs[1, 1], image_id=4, data_list=sampled_paths)

render_chart(fig=fig, axis=axs[1, 2], image_id=5, data_list=sampled_paths)

In this case the number of unique characters present in the sample is 4, which we are setting as target value to be learnt by the model.

And here is how we can combine the building blocks we have written above to create more complicated models:

from tensorflow.keras.layers import LayerNormalization, Dense

import tensorflow as tf

from set_transformer.layers.attention import MultiHeadAttention

from set_transformer.layers import RFF

from set_transformer.blocks import SetAttentionBlock, PoolingMultiHeadAttention

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Conv2D

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Conv2D, Input, MaxPooling2D, Dropout, Flatten

from tensorflow.keras.models import Model

tf.keras.backend.set_floatx('float32')

def image_processing_model(input_image_shape = (105, 105, 1), output_len=128):

input_image = Input(shape=input_image_shape)

y = Conv2D(64, kernel_size=(3, 3),

activation='relu',

input_shape=input_image_shape)(input_image)

y = Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu')(y)

y = Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu')(y)

y = Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu')(y)

y = MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2))(y)

y = Dropout(0.25)(y)

y = Flatten()(y)

output_vec = Dense(output_len, activation='relu')(y)

return Model(input_image, output_vec)

class CharEncoder(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, d=64, h=8):

super(CharEncoder, self).__init__()

# Instantiate image processing model

self.image_model = image_processing_model(output_len=d)

# Encoding part

self.sab_1 = SetAttentionBlock(d, h, RFF(d))

self.sab_2 = SetAttentionBlock(d, h, RFF(d))

def call(self, x):

return self.sab_2(self.sab_1(tf.map_fn(self.image_model, x)))

class CharDecoder(tf.keras.layers.Layer):

def __init__(self, out_dim, d=64, h=8, k=32):

super(CharDecoder, self).__init__()

self.PMA = PoolingMultiHeadAttention(d, k, h, RFF(d), RFF(d))

self.SAB = SetAttentionBlock(d, h, RFF(d))

self.output_mapper = Dense(out_dim)

self.k, self.d = k, d

def call(self, x):

decoded_vec = self.SAB(self.PMA(x))

decoded_vec = tf.reshape(decoded_vec, [-1, self.k * self.d])

return tf.reshape(self.output_mapper(decoded_vec), (tf.shape(decoded_vec)[0],))

class CharSetTransformer(tf.keras.Model):

def __init__(self):

super(CharSetTransformer, self).__init__()

self.encoder = CharEncoder()

self.decoder = CharDecoder(out_dim=1)

def call(self, x):

enc_output = self.encoder(x) # (batch_size, set_len, d_model)

return self.decoder(enc_output)

Conclusion

I encourage you to read the original paper (complete with supplementary materials) where the authors show useful theoretical properties of the Set Transformer, , including the fact that it is a universal approximator for permutation invariant functions.

I was also surprised to see that among the future developments of this work they suggest that Set Transformer can be used to meta-learn posterior inference in Bayesian models (did not see that coming!)

Reference

- “Attention is all you need”, 2017, https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762

- “Set Transformer: A Framework for Attention-based Permutation-Invariant Neural Networks”, 2019, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.00825.pdf

- “Graph transformer networks”, 2019, https://papers.nips.cc/paper/9367-graph-transformer-networks.pdf

Equation editor

- https://www.codecogs.com/latex/eqneditor.php (Latin Modern, 12pts, 150 dpi)