The Choose-Explore-Unchoose pattern for backtracking

On how a simple exercise can help you tackle backtracking questions

Backtracking tries to find out the solution to a given problem by moving in various directions (or tree paths) and rejecting those directions that do not give us the required solution. I will just start with a simple (yet more rigorous) definition from Wikipedia:

Backtracking is a general algorithm for finding all (or some) solutions to some computational problems, that incrementally builds candidates to the solutions, and abandons each partial candidate (“backtracks”) as soon as it determines that the candidate cannot possibly be completed to a valid solution.

This definition may seem pretty straightforward if you have had some experience with backtracking, but the truth is that backtracking questions can get pretty difficult to solve sometimes. For this reason I would like to propose a real-world example (at least, in the coding-interview world) and solve it with a method that can help you spot and easily frame backtracking exercises. The problem I am referencing here from Leetcode is the classical ‘permutations problem’, i.e. given an array containing n numbers or letters generate all the possible permutations (we know from statistics that the number of permutations for n objects is equal to the factorial of n, n!).

Statement of the problem:

Input: [1,2,3]

Output:

[

[1,2,3],

[1,3,2],

[2,1,3],

[2,3,1],

[3,1,2],

[3,2,1]

]

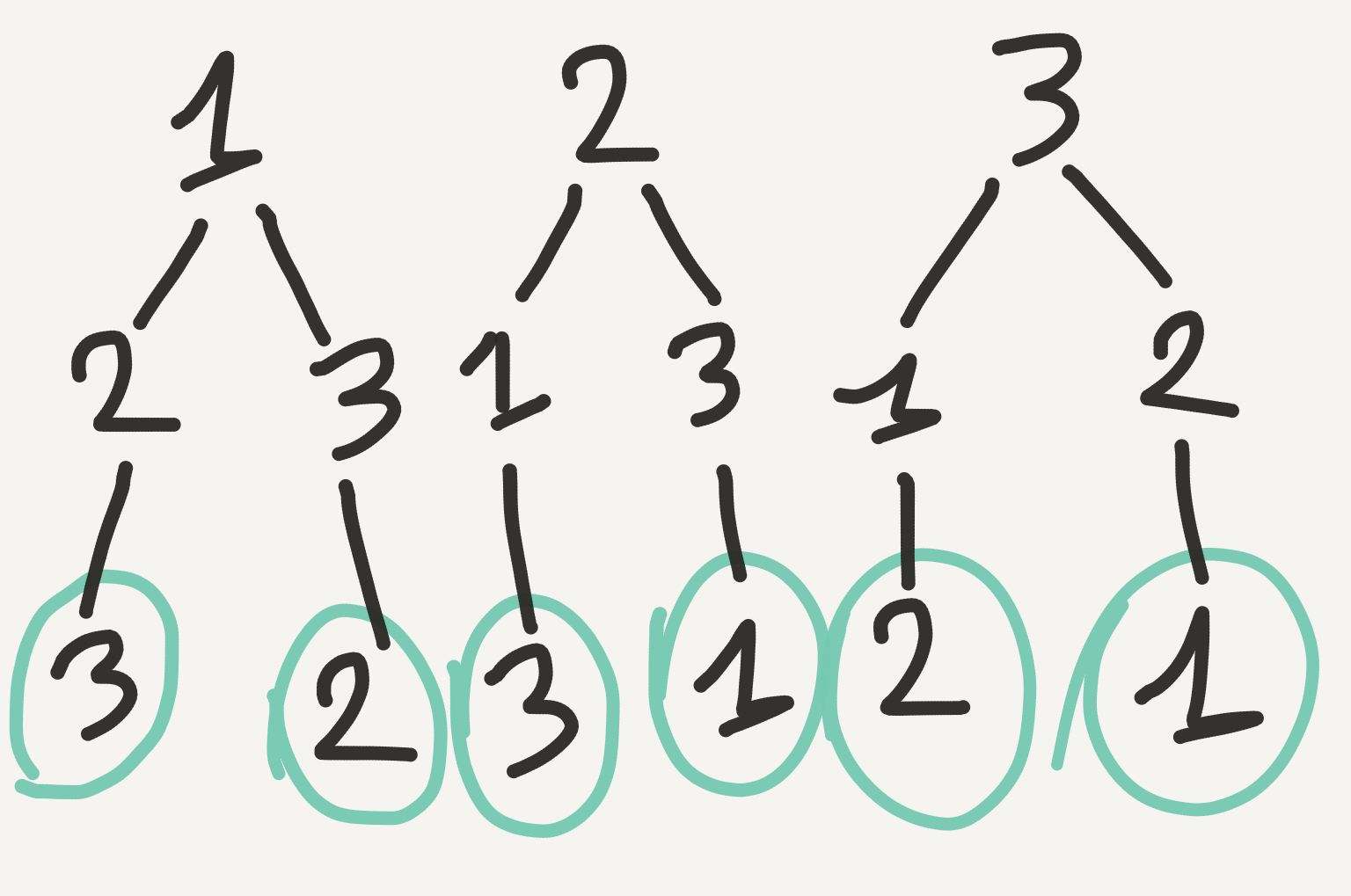

Let us try to picture the different choices/permutations we get when dealing with permutations (fig.1):

In this representation each ‘chain’ of subsequent numbers [[1,2,3], [3,2,1]…] represents a permutation that our program will explore and output. The green circle around the last position in the graph means that our program (when generating permutations) will stop when the length of the current branch is equal to the length of the input array [1,2,3]. This may sound trivial, but it is essentially what we need as ‘termination condition’ of our recursive exploration. We also see that a simple strategy to generate all possible permutations is to put in the first position of our sequences the numbers of the input list in turn, and from there permute sub-sequences excluding the ‘head of the chain’, i.e. the selected number.

We now write the code using a simple yet very useful pattern for graph exploration (which I got from a lesson of the Stanford CS 106B course on Youtube): it is called “choose-explore-unchoose”, and can be described in the following way:

- Use an iterator to list all the possible starting points for our recursion (every number in our list) (the ‘for’ loop in the explore_helper function below)

- ‘Choose’: select one number by adding it to a stack that holds the current branch

- ‘Explore’: recursively call the ‘explore_helper’ function which will carry on the recursion and pass along the stack which contains the numbers chosen in the current branch

- ‘Unchoose’: remove the recently added number and go back to step 1 to explore another sub-branch. The termination condition that will stop the recursion and add the current branch to the ‘results’ list is given (as previously stated) by the comparison between the length of the branch and the length of the original list to permute ([1,2,3])

With this code we are recursively exploring a graph just by selecting an item (choose), calling a function that will carry on the recursion (explore) and going back to where we came from (unchoose) to explore another sub-branch of the graph until we are done. In this process we are keeping track of the paths we have chosen, saving only those ending with a ‘terminal leaf’ of the graph.

This is a Python solution that passes the test cases in 25 ms (a bit slow, I will tell you later about performance):

class Solution:

def permute(self, nums):

"""

:type nums: List[int]

:rtype: List[List[int]]

"""

if not nums: return []

results=[]

self.explore_helper(nums, results)

return results

def explore_helper(self, alist, results, partial_result=[]):

if len(partial_result) == len(alist):

results.append(partial_result.copy())

else:

for i in range(len(alist)):

if alist[i] in partial_result: continue

partial_result.append(alist[i]) # CHOOSE

self.explore_helper(alist, results, partial_result) # EXPLORE

partial_result.pop() # UNCHOOSE

One thing to notice here is that we are using a Python list to hold the ‘explored’ solutions and then we are checking on line 17 if our number is already contained in it (we want to avoid repetition in permutations). Unfortunately, every time we execute this command Python needs to go through every item contained in the list, making this step O(n). Just use an extra Python set to hold the selected numbers, making this step O(1).

Here is another exercise also taken from Leetcode where we need to generate the power set of a set of distinct numbers, i.e. the list of all possible subsets.

Input: nums = [1,2,3]

Output:

[

[3],

[1],

[2],

[1,2,3],

[1,3],

[2,3],

[1,2],

[]

]

And here is the solution using the same CHOOSE-EXPLORE-UNCHOOSE pattern:

class Solution:

def subsets(self, nums):

"""

:type nums: List[int]

:rtype: List[List[int]]

"""

if not nums: return []

results = []

self.subset_helper(nums, results)

return results

def subset_helper(self, nums, results, partial_list=[], start_index=0):

results.append(partial_list.copy())

for i in range(start_index, len(nums)):

partial_list.append(nums[i]) # CHOOSE

start_index+=1

self.subset_helper(nums, results, partial_list, start_index) # EXPLORE

partial_list.pop() # UNCHOOSE

The implementation is very similar to what we saw for permutations, although now we do not need to state a termination condition at the beginning of the helper function. We introduce instead a ‘start_index’ variable that is used inside the iterator: the index is increaased at every step of recursion, which means that after n steps is going to be equal to length of ‘nums’ and just stops.

What kind of other problems can we tackle by using this approach to backtracking? Well, examples that come to mind are the maze exploration (another classical algorithm of this class) and the eight queens puzzle, but (unless I will be proven wrong) this approach can be extended to all algorithms where backtracking/dynamic programming is required.